The architecture behind a reliable AI-powered system

Lessons from building production AI-powered systems: intent classification, guardrails, caching, and feedback loops

For the past couple of months, I’ve been working on AI-powered systems and chatbots at my workplace. With minimal knowledge of architecting and building such systems, I had to rely on online tutorials and books to try to find the best way to build. For the most part, these didn’t help much, so I resorted to bulldozing through, figuring things out as I went.

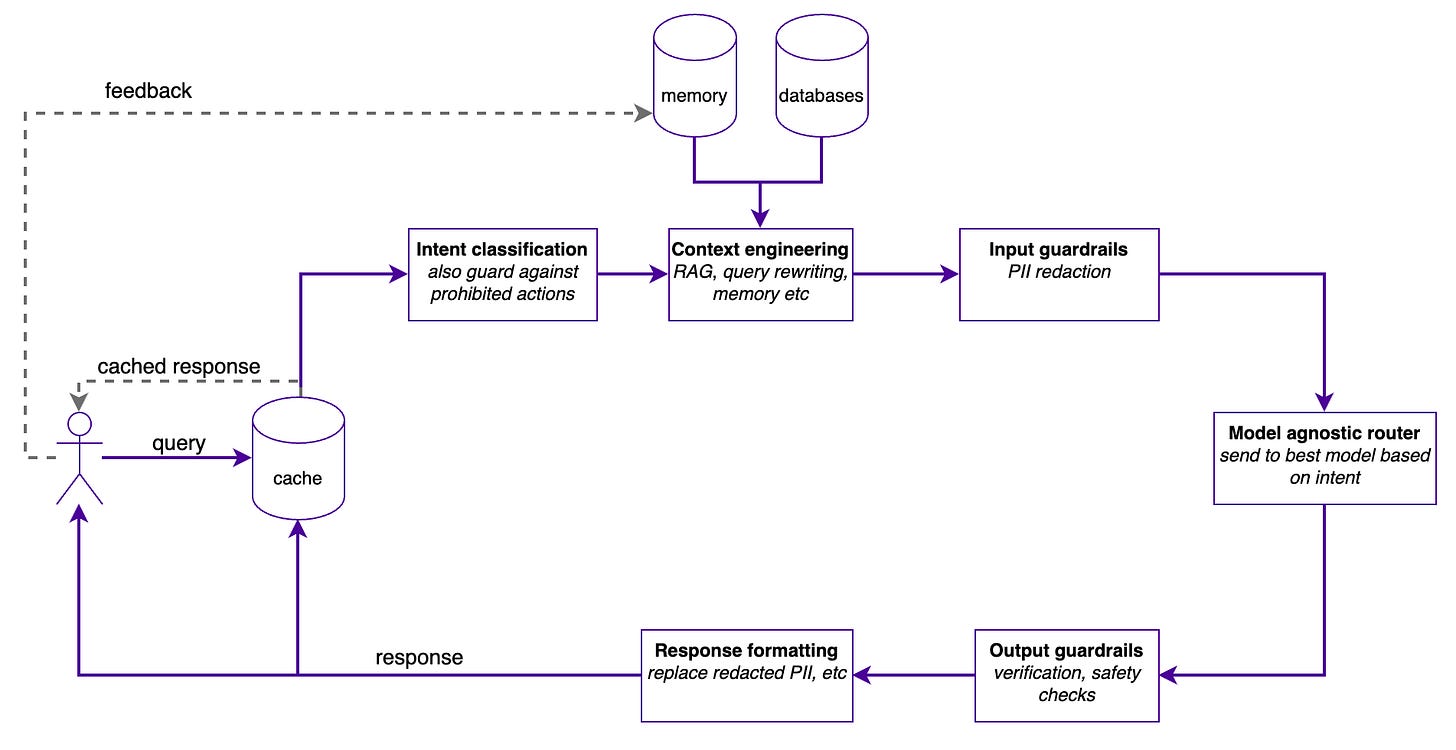

Below is the architecture I’ve landed on. It’s definitely not the only way, and I’m convinced it’ll improve over time. It’s been battle-tested, and so far, it covers the gaps that I found in most tutorials.

The full picture

The query flows through several stages before a response reaches the user. Each stage exists because I learned the hard way what happens when you skip it.

Let’s walk through each one.

1. Cache

The first thing a query hits is the cache. Why? Because everything downstream is expensive. RAG lookups, LLM calls, guardrail checks — all of it costs time and money.

This isn’t just key-value caching. For AI systems, you need semantic caching — matching queries by meaning, not exact string matches. “What’s your refund policy?” and “How do I get my money back?” should hit the same cache entry.

Implementation notes:

Embed incoming queries and compare against cached query embeddings

Set a similarity threshold — too low, and you return wrong answers, too high, and you rarely hit cache

Cache responses with TTL based on how often the underlying data changes. One thing I’m thinking of doing is deciding intelligently what to cache and what not to.

Invalidate aggressively when source data updates

2. Intent classification

Before you do any expensive context retrieval, classify what the user actually wants. This serves two purposes:

Routing: Different intents need different handling. A simple FAQ lookup doesn’t need your most powerful model. A complex analysis might need multiple tool calls. Classify first, then route appropriately.

Safety: This is your first line of defence against prohibited actions. If someone’s trying to extract training data, bypass restrictions, or do something harmful, catch it here before you’ve spent compute on context retrieval.

I run a very small model at this stage — fast enough not to add meaningful latency, but accurate enough to catch the obvious cases. The heavy-duty safety checks come later in the guardrails.

What intent classification catches:

Query type (question, clarification, feedback)

Domain routing (which knowledge base or tool set applies)

Risk signals (prompt injection attempts, out-of-scope requests)

3. Contex engineering

This is where your RAG pipeline, memory systems, and query rewriting live. The goal: construct the context that gives the model the best chance of generating a helpful response. The user’s intent from the previous step informs what information needs to be added to the context.

Query rewriting: User queries are often ambiguous or incomplete. “What about the deadline?” means nothing without context. Rewrite queries to be self-contained using conversation history.

RAG retrieval: Pull relevant documents, generate and run database queries. Retrieve what’s actually relevant based.

Memory: This includes both short-term and long-term memory. For multi-turn conversations or returning users, inject relevant history. What did they ask before? What preferences have they expressed? This is especially important for personalisation. In a natural language-to-SQL (nl2sql) system I built, I use data from long-term memory for few-shot prompting. Based on users’ feedback from previous interactions, I’d add a few examples of good queries, as well as bad queries and reasons why they are good or bad.

The key insight: Context engineering is where most of your system's “intelligence” comes from. A mediocre model with great context beats a great model with poor context.

4. Input guardrails

Now the query has context; before it goes to the model, run it through input guardrails. One of the primary concerns here: privacy

If your context includes personally identifiable information (PII) or any other sensitive data, you need to redact it before sending it to the LLM. This is non-negotiable for most production systems.

How I handle PII:

Named entity recognition to identify PII

Replace with deteministic placeholders ([CUSTOMER_<hash>], [EMAIL_<hash>], etc.)

Store a mapping in the conversation scope so you can restore the original values before sending a response to the user.

The mapping never leaves your system — only the redacted text goes to the model.

Input guardrails also catch anything the intent classifier missed. If a carefully crafted prompt injection made it past classification, this is your second chance to see it.

5. Model agnostic router

Not every query needs your most expensive model. The router decides where to send the request based on:

Complexity: Simple lookups go to faster, cheaper models. Complex reasoning goes to more capable ones.

Intent: Code generation might route to a model fine-tuned for code. Creative writing, tuned for that.

Cost constraints: If you have token budgets, the router enforces them.

I call this “model agnostic” because the rest of the system doesn’t care which model handles the request. The router abstracts that decision away.

Practical tip: Start with a single model and add routing later. Premature optimisation here adds complexity without proven benefit. Use a router when you have data showing that different queries need different handling.

6. Output guardrails

The model has generated a response. Before it reaches the user, verify it.

Factual grounding: If the response makes claims, can you trace them back to the retrieved context? Flag or filter responses that hallucinate beyond what the context supports.

Safety checks: Run the response through content classifiers. Does it contain anything harmful, inappropriate, or policy-violating? Catch it here.

Format validation: If you expected structured output, validate it. Malformed responses should retry or fallback, not reach the user.

Consistency checks: Does the response contradict earlier statements in the conversation? Does it make promises your system can’t keep?

A very small model can be used here to minimise latency.

7. Response formatting

Final stage: prepare the response that will be sent to the user.

PII restoration: Remember those placeholders? Replace them with the original values from your mapping. The user sees real names and data; the model only ever saw redacted versions.

Then cache the response (if appropriate) and return to the user.

The Feedback Loop: Learn and Improve

One piece I haven’t mentioned: the feedback loop.

User feedback — explicit (thumbs up/down, ratings) and implicit (follow-up questions, task completion) — flows back into your system. This informs:

Cache invalidation: If users consistently dislike a cached response, invalidate it.

Memory updates: Store what worked and what didn’t for future context

Retrieval tuning: If certain documents consistently lead to inadequate responses, adjust their ranking

Model routing: If one model consistently performs better for certain query types, update routing rules

This is how your system gets smarter over time without retraining models.

Principles Behind the Architecture

A few principles that shaped these decisions:

Fail early, fail cheap: Catch problems as early as possible in the pipeline. Intent classification and cache checks are cheap. Model inference is expensive. Don’t spend the expensive compute on queries you’re going to reject anyway.

Defence in depth: Don’t rely on any single safety mechanism. Intent classification, input guardrails, and output guardrails all catch different things. Overlap is fine — missing something isn’t.

Separate concerns: Each stage has one job. Context engineering doesn’t know about caching. Guardrails don’t know about routing. This makes the system testable and maintainable.

Make it observable: Every stage should emit metrics such as cache hit rates, guardrail trigger rates, model latencies, and feedback signals. You can’t improve what you can’t measure.

What I’d Do Differently

If I were starting over:

Add semantic caching earlier. I underestimated how much duplicate work we were doing.

Invest more in intent classification. A good classifier up front saves so much complexity downstream.

Build the feedback loop from day one. Feedback makes the system self-improve over time.

Wrapping Up

This architecture isn’t perfect, and it’s certainly not the only way to build production AI-powered systems. But it handles the problems I kept running into: sensitive data, expensive inference, unreliable outputs, and the need to improve over time.

The pattern applies whether you’re building a customer support bot, a document analysis tool, or an internal knowledge assistant — the specific implementations change; the stages don’t.

If you’re building something similar, I’d love to hear what’s working for you. What am I missing? What would you do differently?